What do you do when your out-of-house contract designer phones it in, but it is your team that will be the one to pay the consequences for years to come? This is exactly the question we were faced with at the beginning of 2019, during an exhibit refresh of Woodland Park Zoo’s Northern Trail. Plagued with complication after complication, this project could not support another delay and I was forced to step up and step in to protect the integrity of the portion of the project that was in my control.

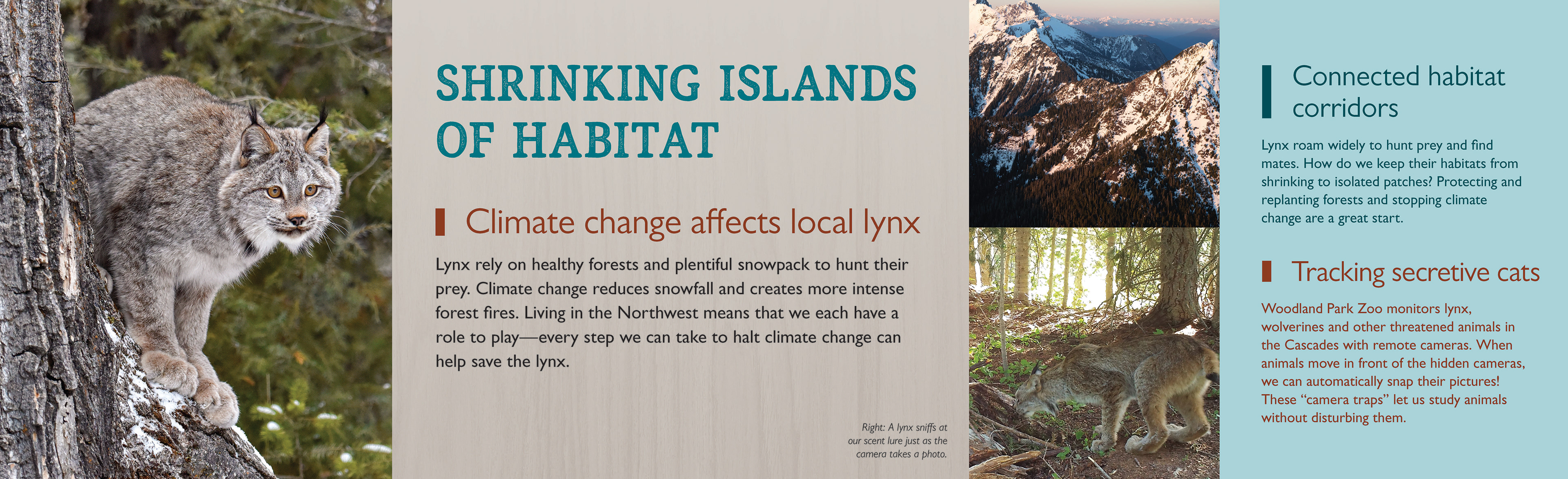

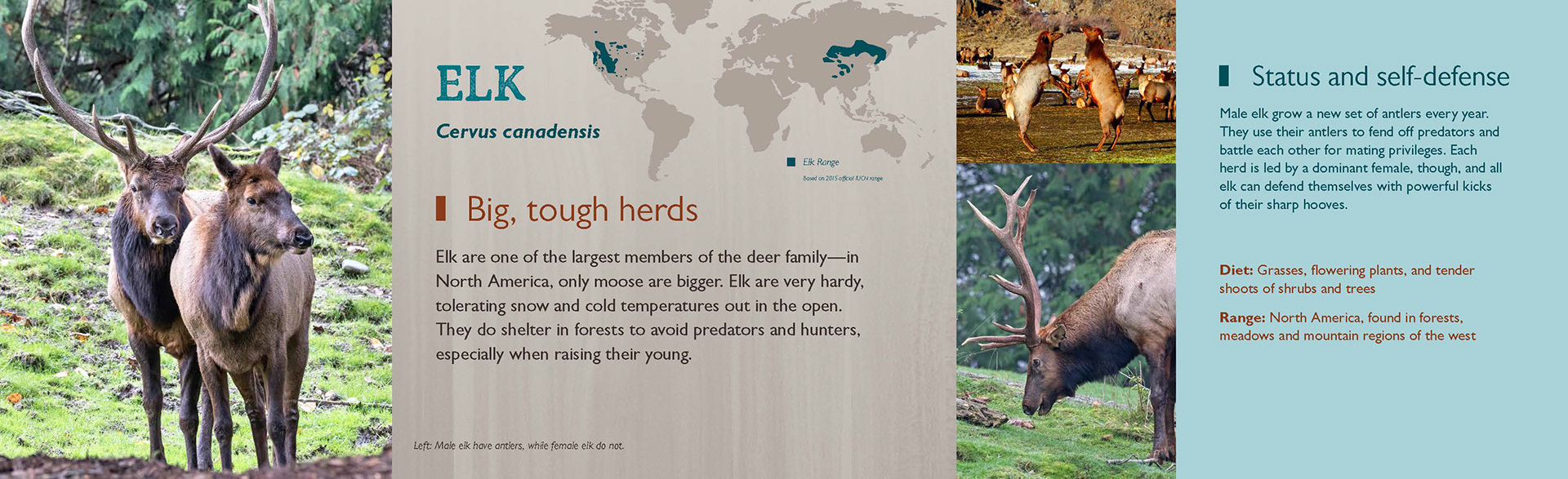

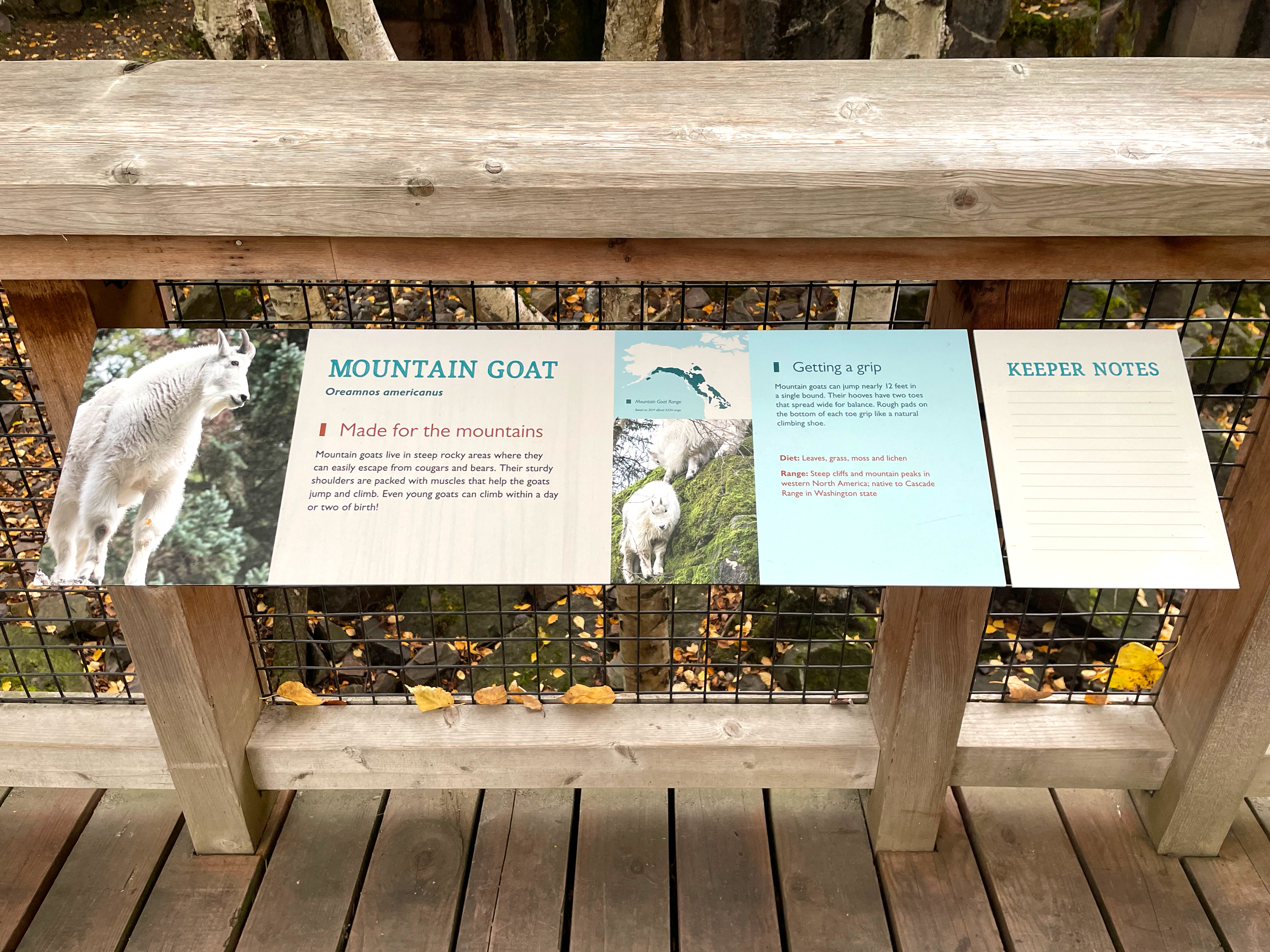

Understaffed, rushed, and a bit cursed, this project was in triage mode by the time I was brought on board to provide input and direction for the new exhibits interpretive signage designed out-of-house. Earlier in the year, I had virtually conferenced with the firm that had been commissioned to handle the zoo’s interpretive signage for the exhibit’s scheduled refresh. We discussed the zoo’s brand and our immersive design strategies, but months later, snuggly bordering the point of no return, they came back with designs (and content) no one was happy with. This left the zoo in a very difficult position. Send the firm to start over again from scratch, which we did not have time for; move forward with content and design that did not live up to the zoo’s expectations, which would look bad for the zoo’s first exhibit of their new capital campaign; or step in and take control.

I had many serious talks with the Project Managers, but in the end, we all agreed that our Creative Studio could move far more nimbly and accurately than the firm to provide clear direction that the project needed to take. We got to work right away and within a week and a half had created several cohesive and elegant templates for use within the exhibit. Now came the hard part. Since this project came to my team so quickly and without the opportunity to plan accordingly, there was no way for us to accommodate the capacity to build out each and every sign for the exhibit moving forward. We would have to go back to the firm and tell them they had to use our design while producing the exhibit.

Obviously, no designer likes to be told their design isn’t good enough, let alone by an “in-house” designer. And even though the reputation of in-house designers is evolving and growing every day, I’d say the agency ego still exists. This was evident in that first meeting with the firm. In the end, however, despite my instinct to be “nice” I could not let hurt feelings get in the way. The thing about being an in-house designer is this: After the firm has done its job and moves on to the next project, it’s up to the in-house team to maintain the artwork for the rest of its reign. In the case of exhibit design, that can be upwards of 20 years sometimes. I care about my institution too much to see hard work muddied by bad design, and stay firm to the confidence in our design.

In the end, Covid delayed the project another year allowing our in-house team to take over the final phases of production. Though it created more work for our team, I’m content knowing the final details are to my standards.

In the end, Covid delayed the project another year allowing our in-house team to take over the final phases of production. Though it created more work for our team, I’m content knowing the final details are to my standards.